Origins of Human Expression: A Journey Through Ancient Artz

Ancient artz refers to the creative expressions and visual representations produced by early human civilizations from the Upper Paleolithic period (roughly 40,000 BCE) to the early Middle Ages (around 500 CE to 800 CE, depending on the region). This broad period spans thousands of years and includes a variety of cultures across continents, each leaving behind a unique artistic legacy that reveals their beliefs, technologies, and social structures.

Ancient art is not limited to aesthetics alone—it was deeply embedded in daily life, spirituality, and power structures. From cave walls to stone monuments and ceremonial objects, art served as a bridge between the physical and metaphysical.

Purpose and Function

The purpose of ancient art was multi-faceted, with functions that often overlapped:

-

Religious & Spiritual: Most early art had a sacred function, used in worship, burial practices, and to honor gods, spirits, or ancestors. Examples include tomb paintings in Egypt or totemic carvings in tribal societies.

-

Ceremonial & Ritualistic: Masks, amulets, idols, and altars were crafted for use in specific ceremonies or seasonal events, such as fertility rites or funerals.

-

Political & Propagandistic: Kings, pharaohs, and emperors commissioned grand statues and monuments to project divine authority and social order (e.g., Hammurabi’s Stele, Roman triumphal arches).

-

Symbolic: Art encoded symbols to communicate ideas of power, eternity, purity, or chaos, often through shapes, animals, or mythological motifs.

-

Utilitarian & Decorative: Everyday items like pottery, tools, and textiles were adorned with motifs that reflected local culture, serving both function and form.

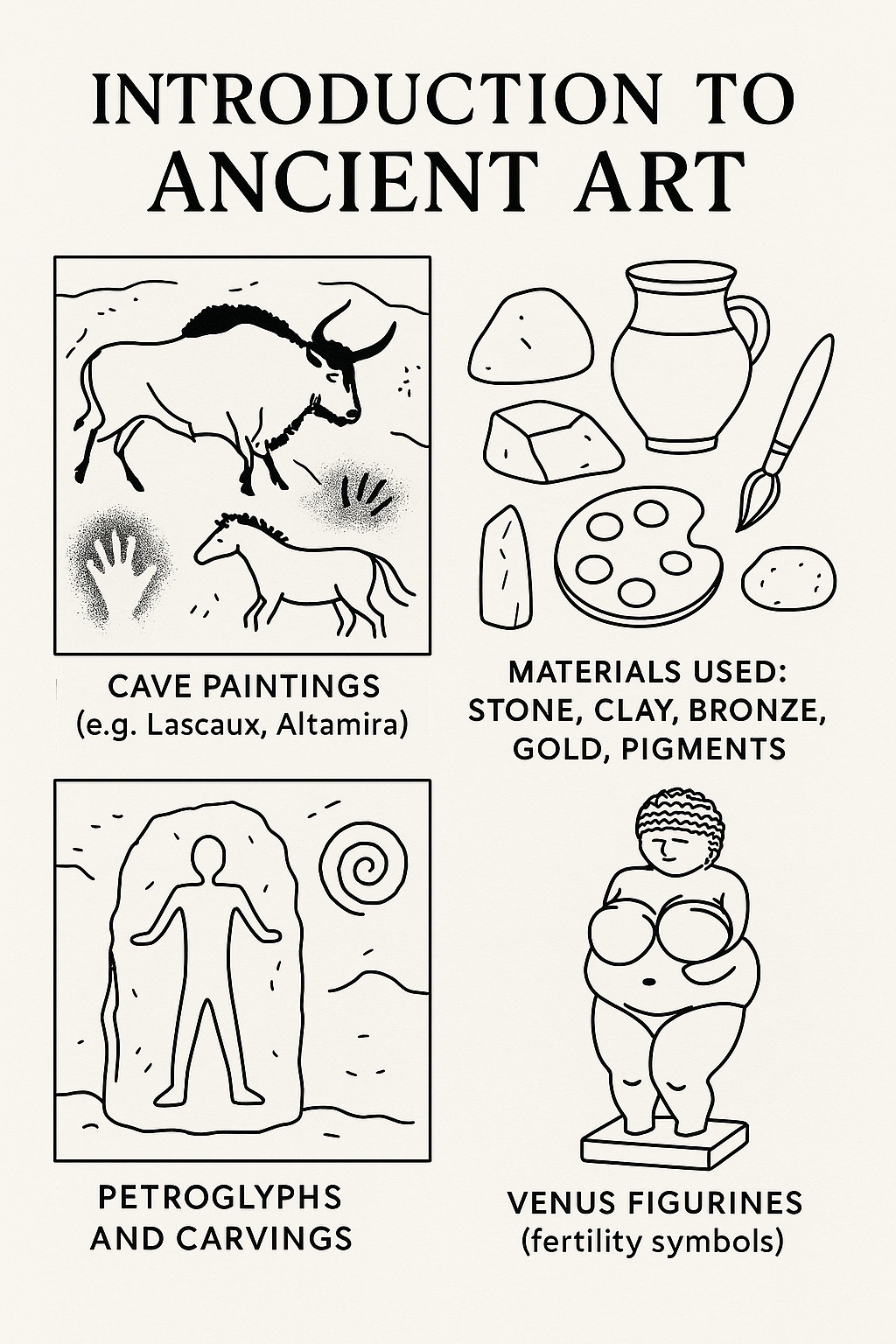

Materials and Techniques Used

Early civilizations demonstrated impressive ingenuity with limited tools, using what was available in their environment:

-

Stone: Used for carving statues, tools, temples, and megaliths. Hard stones like basalt and granite were used in Egypt and Mesoamerica for durable monuments.

-

Clay: Easily molded and fired into vessels, tablets, and figurines. Terracotta was widespread in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and Greece.

-

Bronze: Heralding the Bronze Age, this alloy was used for weapons, jewelry, ritual objects, and later sculptures, offering greater detail and durability.

-

Gold & Precious Metals: Reserved for royalty and religious elites, gold symbolized immortality or divine power. Notably used in Egyptian burial masks and Andean ceremonial items.

-

Pigments: Derived from natural minerals (ochre, charcoal, lapis lazuli), pigments were used in cave paintings, murals, and decorative pottery. These pigments were mixed with binders like fat, egg, or resin to adhere to surfaces.

Prehistoric Art

Cave Paintings

Cave paintings are some of the earliest surviving expressions of human creativity, dating as far back as 40,000 BCE. These artworks were often located deep within cave systems, away from natural light, suggesting a ceremonial or spiritual purpose.

Notable sites:

-

Lascaux Cave (France): Discovered in 1940, it features vibrant depictions of bulls, deer, and horses, painted using ochre and charcoal. The precision of movement and shading implies a surprisingly advanced understanding of animal anatomy and artistic composition.

-

Altamira Cave (Spain): Celebrated for its polychrome (multi-colored) bison, created with blown pigments and natural contours of the cave surface to enhance three-dimensionality.

These images may have served ritualistic or sympathetic magic purposes—early humans possibly believed that depicting a successful hunt would help manifest it in reality.

Petroglyphs and Carvings

Petroglyphs are images carved or pecked directly into rock surfaces. Unlike cave paintings, they are often found in open-air locations and can span across continents, from the American Southwest to Australia and Scandinavia.

These carvings include:

-

Abstract patterns (spirals, zigzags, grids)

-

Animal figures (elk, mammoths, birds)

-

Human forms, often stylized or exaggerated

They likely functioned as a form of proto-writing, storytelling, spiritual mapping, or tribal marking. Some sites also align with astronomical events, such as solstices.

Venus Figurines

“Venus figurines” is a modern term used to describe small Paleolithic statuettes of women, emphasizing exaggerated reproductive features—wide hips, large breasts, and rounded abdomens.

Examples include:

-

Venus of Willendorf (Austria, ~28,000 BCE)

-

Venus of Hohle Fels (Germany, ~35,000 BCE)

These figurines were likely fertility symbols or mother goddess representations, reflecting the importance of childbirth and survival in prehistoric communities. Their portability suggests they may have served as personal talismans or ritual items.

Mesopotamian Art

Ziggurats and Temple Architecture

Mesopotamian architecture was deeply tied to religion and kingship, with ziggurats serving as the most iconic structures. These massive, terraced step-pyramids were built with sun-dried mud bricks and featured ascending platforms meant to bridge heaven and earth.

-

Each city-state had its own patron deity, and the ziggurat formed the center of both civic and spiritual life.

-

Example: Ziggurat of Ur (~2100 BCE), built in honor of the moon god Nanna, rises in three tiers and was accessed by grand stairways.

-

Ziggurats were not temples themselves but raised platforms supporting a temple shrine at the top—believed to be the god’s earthly dwelling.

Architecturally, these structures established the axis mundi (cosmic axis), linking the heavens, earth, and underworld—a concept central to Mesopotamian cosmology.

Reliefs: War, Kingship, and Mythology

Mesopotamian reliefs—especially from Assyrian and Babylonian palaces—combined artistic mastery with political propaganda.

-

Assyrian Lion Hunt Reliefs from Nineveh (c. 645 BCE) show King Ashurbanipal engaging in ritual lion hunts, symbolizing his divine right to rule and dominance over chaos.

-

Mythological scenes often depict gods, monsters, and cosmological battles—such as the Epic of Gilgamesh narrative rendered in clay tablets and architectural carvings.

-

Narrative reliefs functioned like visual chronicles, often arranged in horizontal bands (registers) that showed sequences of military campaigns, tribute offerings, and royal conquests.

These artworks emphasize hierarchical proportion—the king appears significantly larger than other figures, underscoring his supreme status.

Cylinder Seals

Cylinder seals were small, cylindrical objects carved with intricate scenes and inscriptions, typically made of lapis lazuli, hematite, or chalcedony.

-

Used to mark ownership, authenticate documents, and protect containers or doors with a signature.

-

When rolled across wet clay, the cylinder left behind a continuous impression—a miniature narrative or divine invocation.

-

Designs often included gods in profile, sacred animals, worshippers, and celestial symbols (such as the winged sun disk or crescent moon).

These tiny objects were both functional tools and works of high craftsmanship, often worn as pendants and passed down through generations.

Key Artifacts

Stele of Hammurabi (c. 1754 BCE)

-

A black diorite stele standing over 7 feet tall, inscribed with one of the earliest known legal codes.

-

The upper portion features Hammurabi receiving divine authority from the sun god Shamash, symbolizing law as a divine gift.

-

The text beneath details over 280 laws related to justice, trade, family, and punishment, reinforcing the king’s role as lawgiver and protector.

Standard of Ur (c. 2600–2400 BCE)

-

A wooden box from a royal tomb in Ur, inlaid with lapis lazuli, red limestone, and shell.

-

Its two panels—”War” and “Peace“—present vivid mosaics of battle scenes, captured enemies, feasting, and gift-giving.

-

The work illustrates a complex, stratified society, showing the coordination of military power and ceremonial harmony, possibly used as a soundbox or military emblem.

Egyptian Art

Tombs, Pyramids, and Funerary Art

Egyptian art is inseparable from the cult of the afterlife. The architecture and decoration of tombs were intended to secure the soul’s journey through the underworld and ensure a comfortable eternity.

-

Pyramids (like those at Giza) were royal tombs, massive feats of engineering meant to reflect cosmic order and divine kingship. Their precise alignment with celestial bodies emphasized the pharaoh’s godlike role.

-

Mastabas (flat-roofed tombs) and rock-cut tombs were elaborately decorated with carvings and painted scenes of daily life, agriculture, and ritual offerings—each representing activities the deceased hoped to enjoy in the afterlife.

-

Funerary art included canopic jars, amulets (e.g., scarabs, ankhs), sarcophagi, and shabti figures—miniature servants meant to work for the deceased in the afterlife.

These works weren’t just artistic—they were magical tools, guided by religious texts and ritual conventions.

Wall Paintings and Hieroglyphics

Egyptian wall paintings were characterized by order, clarity, and symbolism, typically created with mineral-based pigments on plaster.

-

Hieroglyphics, a sacred writing system, were often integrated into the composition. Rather than mere text, they were believed to hold spiritual power, with certain signs representing gods or sacred concepts.

-

Scenes were arranged in registers (horizontal bands), often depicting pharaohs performing rites, receiving tribute, or interacting with gods.

-

Composite view was common—heads and legs shown in profile, torsos front-facing—designed for clarity and spiritual function, not realism.

Such paintings weren’t decorative but ritual blueprints, reinforcing cosmic balance and continuity.

Statues of Gods and Pharaohs

Sculpture in Egypt had both a representational and spiritual function. Statues were created not to be viewed, but to house the ka (spirit) of gods, kings, or the deceased.

-

Pharaohs were sculpted in idealized, eternal youth to emphasize their divine nature. Common poses included seated, striding forward, or with arms crossed holding crook and flail.

-

Gods like Osiris, Horus, and Anubis were rendered in hybrid forms—part human, part animal—to reflect their symbolic powers.

-

Materials like diorite, granite, and alabaster were chosen for durability, as permanence was essential in funerary art.

Even in miniature, statues served as eternal vessels for identity and divine presence.

Symbolism in Egyptian Art

Egyptian art operated on a symbolic system, visually encoding religious and philosophical concepts:

-

Ma’at: The principle of universal order, balance, and truth—often depicted as a goddess with a feather. Ma’at governed both cosmic and societal harmony and was central to all art.

-

Eternal life: Represented by ankhs, rising suns, lotus blossoms, and recurring images of rebirth and renewal (e.g., scarabs pushing the sun across the sky).

-

Color carried deep meaning: Green for rebirth, gold for divinity, blue for the heavens, and red for power or chaos.

Symbolism ensured that art remained more spiritual utility than mere visual expression.

Notable Works

Bust of Nefertiti (c. 1345 BCE)

-

Created by the sculptor Thutmose, this limestone bust captures Queen Nefertiti’s beauty and elegance during the Amarna period.

-

It exemplifies the shift toward naturalism and grace under Akhenaten’s rule, contrasting the rigid forms of earlier dynasties.

-

The asymmetry (one missing eye) is debated—possibly a deliberate ritual choice or an unfinished work.

Book of the Dead

-

A collection of funerary spells, incantations, and illustrations intended to help the deceased navigate the underworld (Duat).

-

Typically written on papyrus scrolls and buried with the dead, it included iconic scenes like the Weighing of the Heart, where the heart is balanced against the feather of Ma’at.

-

Served as a spiritual guidebook, combining text and imagery to ensure moral righteousness and passage to eternal life.

Greek Art

Periods: Geometric, Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic

Greek art evolved in distinct phases:

- Geometric Period (c. 900–700 BCE): Characterized by abstract motifs, meanders, and stylized human figures, primarily on pottery.

- Archaic Period (c. 700–480 BCE): Introduction of kouros and kore statues—rigid, frontal figures with archaic smiles. Influence of Egyptian statuary is evident.

- Classical Period (c. 480–323 BCE): Emphasis on idealized naturalism and harmony. Artists like Phidias and Polykleitos introduced contrapposto and dynamic movement.

- Hellenistic Period (c. 323–31 BCE): Art became more emotional, dramatic, and realistic. Sculptures depicted aging, suffering, and diverse ethnicities.

Idealized Sculpture

Greek sculpture pursued physical perfection:

- Discobolus (Discus Thrower) by Myron: Captures ideal athletic form and dynamic motion.

- Venus de Milo: A Hellenistic masterpiece representing Aphrodite with grace and sensuality, known for its poised, twisting stance and mystery surrounding the missing arms.

Pottery: Black-figure and Red-figure

Greek pottery was both functional and decorative:

- Black-figure technique: Figures painted in black on natural clay, details etched in.

- Red-figure technique: Background painted black, allowing more naturalistic red figures and greater detail.

- Scenes often depicted mythology, daily life, and athletic contests, offering insight into Greek culture.

Architecture: Doric, Ionic, Corinthian

- Doric: Sturdy, plain columns with no base (e.g., Parthenon in Athens).

- Ionic: Slender columns with scroll-shaped capitals.

- Corinthian: Ornate capitals decorated with acanthus leaves, seen in later public buildings. Greek temples balanced symmetry, proportion, and function, reflecting cosmic and civic order.

Roman Art

Adaptation of Greek Styles

Romans borrowed heavily from Greek art but made it more functional and propagandistic, adapting it for empire-wide communication and celebration of power.

Frescoes and Mosaics

- Frescoes: Found in domestic settings (e.g., Pompeii), depicted mythological scenes, landscapes, and daily life.

- Mosaics: Detailed floor and wall images made from colored stones and glass, showcasing elite wealth and craftsmanship.

Portraiture and Realism

- Unlike Greek idealism, Roman portraiture emphasized verism—warts, wrinkles, and all. It celebrated age and experience, especially in busts of statesmen and ancestors.

Public Monuments

- Colosseum: A marvel of engineering and social control; hosted gladiatorial games.

- Arch of Titus: Celebrated Roman military victories with detailed reliefs, like the sack of Jerusalem.

Indian Art

Religious Influence

Indian art is deeply spiritual, drawing from Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, often centered on cosmic balance and reincarnation.

Temples and Stupas

- Temples: Symbolic representations of the universe; rich with carvings and narrative panels.

- Stupas: Dome-shaped reliquaries containing relics of the Buddha (e.g., Sanchi Stupa).

Sculptures

- Depictions of Bodhisattvas, deities, and scenes from sacred texts.

- Use of mudra (hand gestures) and symbolic poses.

Cave Art

- Ajanta and Ellora Caves: Painted and sculpted Buddhist monastic complexes, famous for elaborate wall frescoes and stone reliefs.

Chinese Art

Calligraphy, Bronze, and Jade

- Calligraphy: Considered a supreme art form, combining aesthetics with philosophy.

- Bronze work: Ritual vessels with taotie motifs from Shang and Zhou dynasties.

- Jade carving: Symbolized purity and immortality.

Early Dynasties

- Shang: Ritual bronzes, oracle bones.

- Zhou: Rise of Confucian and Taoist influence.

- Han: Terracotta figures, silk painting, cosmological themes.

Tomb Art

- Terracotta Army: Massive burial complex for Emperor Qin Shi Huang, with life-sized soldiers.

- Silk paintings: Early landscape and spiritual themes.

Philosophical Influence

- Taoism encouraged harmony with nature.

- Confucianism influenced moral and familial depictions in art.

Mesoamerican Art

Civilizations

- Olmec: Colossal stone heads, jade masks.

- Maya: Glyph writing, stelae, and astronomy-linked architecture.

- Aztec: Featherwork, stone carvings, codices.

Architecture

- Pyramid Temples: Step pyramids used for rituals and sacrifices.

- Codices: Illustrated books combining myth, history, and calendars.

Ritualistic Sculpture

- Often depicted gods, warriors, and ceremonial activities.

- Use of bright pigments, symbolism, and human sacrifice themes.

Notable Sites

- Chichen Itza (Maya): Pyramid aligned with equinoxes.

- Teotihuacan: City of the gods, massive pyramids and murals.

African Ancient Art

Rock Art and Carvings

- Found across the Sahara, depicting hunting scenes, rituals, and migrations.

Nok Terracotta

- Nok Culture (Nigeria): Stylized terracotta heads with elaborate hairstyles, possibly ceremonial.

Masks and Figurines

- Used in initiation, ancestor worship, and storytelling.

- Often represent spirits, animals, or cosmic forces.

Symbolism and Worship

- Emphasis on ancestral reverence, fertility, and community harmony.

- Art was participatory—used in dance, music, and oral tradition.

Conclusion

Ancient art was more than decoration; it was a language of belief, power, and identity. These works:

- Encoded the values, myths, and technologies of early civilizations.

- Served as the foundation for religious art, architecture, and visual symbolism across cultures.

- Show that, across time and geography, humans have shared a universal urge to express, immortalize, and transcend.

Frequently Asked Questions: Ancient Art

Q1. What is considered the oldest known form of art?

A1. The oldest known form of art is prehistoric cave painting, such as those in the Chauvet and El Castillo caves, dating back over 30,000 years.

Q2. What materials did ancient humans use for painting?

A2. Early artists used natural materials like ochre, charcoal, hematite, and manganese mixed with animal fat or water to create pigments.

Q3. What were Venus figurines used for?

A3. Venus figurines likely served as fertility symbols or representations of a mother goddess, reflecting prehistoric societies’ emphasis on reproduction and survival.

Q4. Why are petroglyphs important in understanding ancient people?

A4. Petroglyphs offer insight into prehistoric communication, beliefs, rituals, and even early astronomy. They serve as visual records before written language.

Q5. How do archaeologists interpret ancient art?

A5. Interpretation combines context (burial site, tools, rituals), style comparison, and ethnographic studies of indigenous cultures to hypothesize meanings.

Q6. Were ancient artworks created for decoration?

A6. Rarely. Most ancient art served spiritual, ritualistic, or communicative purposes—connecting the living with the divine or with natural forces.

Q7. What does ancient art tell us about early human societies?

A7. It reveals their worldview, priorities (e.g., survival, afterlife, fertility), and capacity for abstract thinking, emotion, and symbolism.

Q8. What are some common themes across ancient cultures?

A8. Common themes include birth, death, fertility, nature worship, myth, cosmic order, and the connection between humans and the divine.